Background History of the Work

A trace is 'a sign that remains to show the former presence of a person or thing no longer there.' (Bloomsbury Dictionary 2005: 1,528). Notions of human existence were developed in the early 1900s by French forensic scientist Edmund Locard to form his thesis that every contact leaves a trace. Subsequently known as 'Rocard's Exchange Principle', this founding work informed the fundamental rule of forensic examination, that residual evidence is always, in all situations, transferred between humans and objects. This premise informs the current practice and supporting research activities.

Conceptual Methodologies

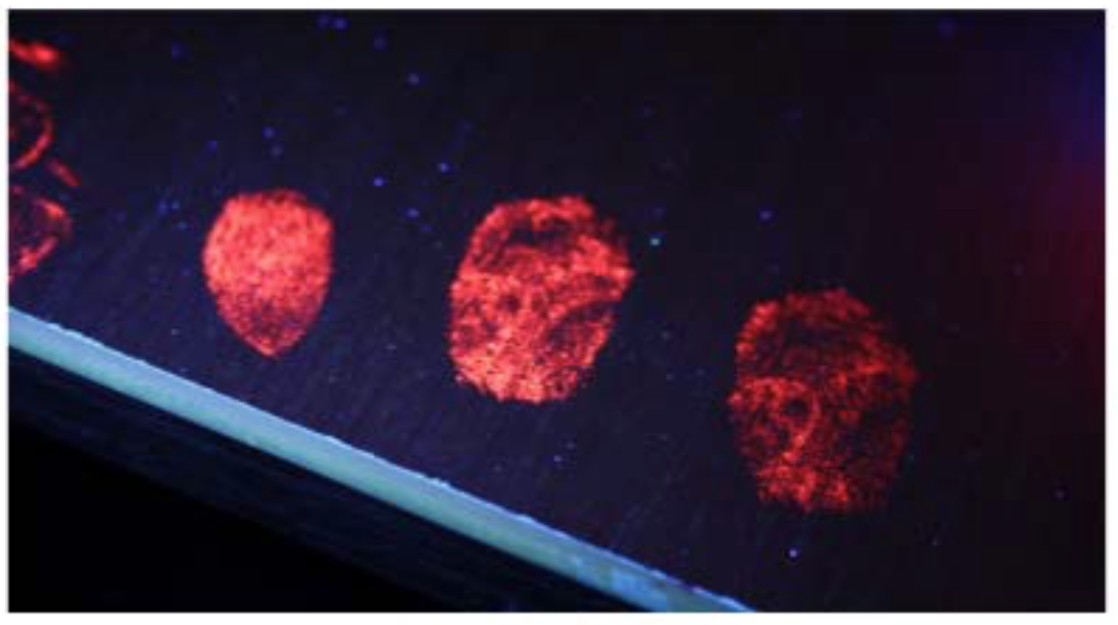

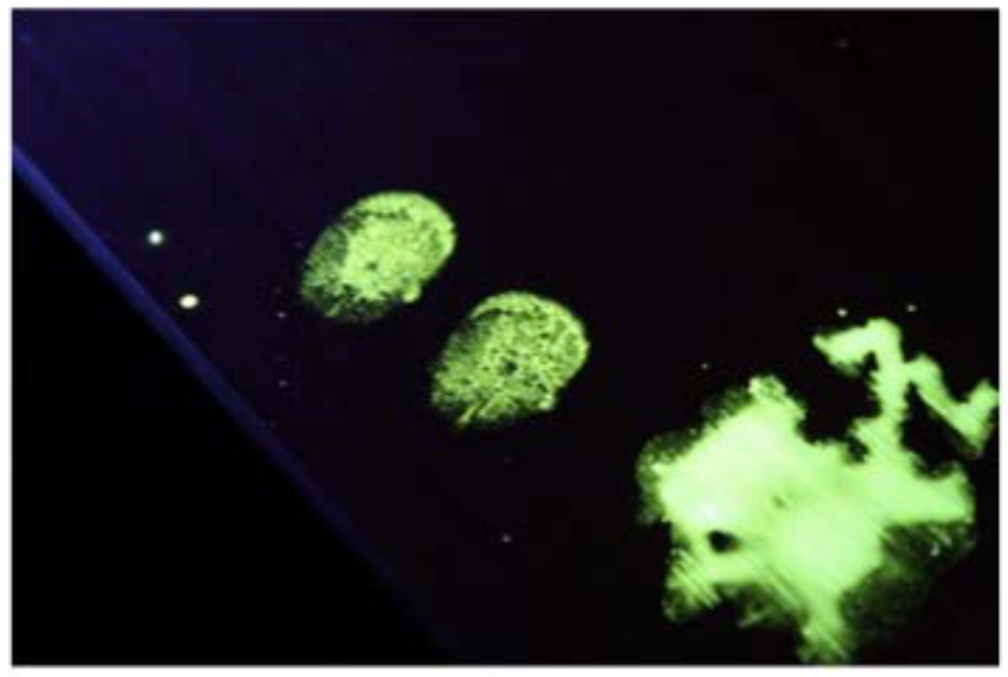

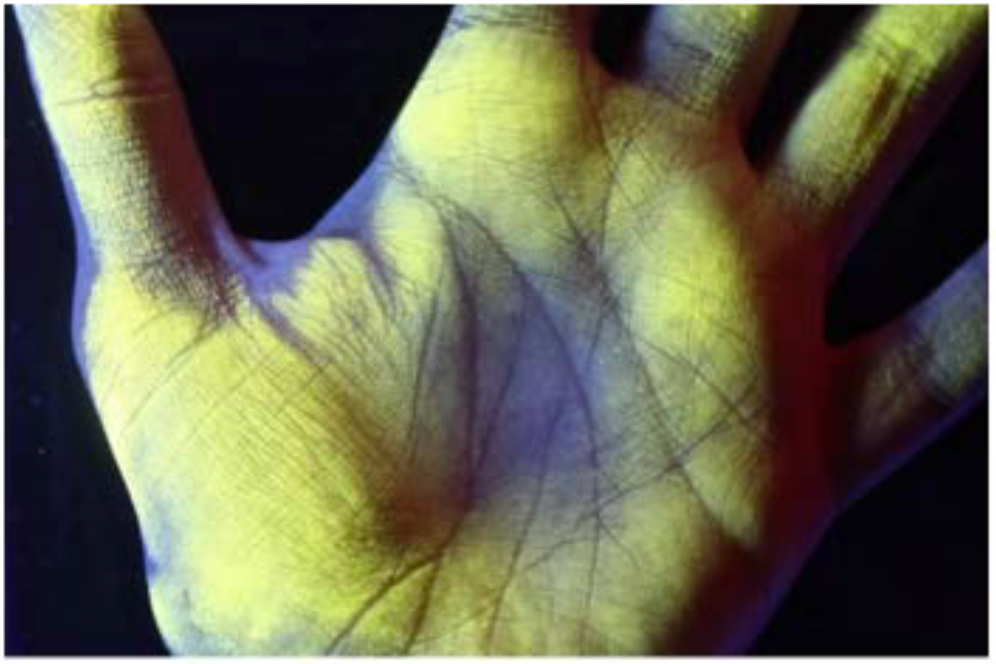

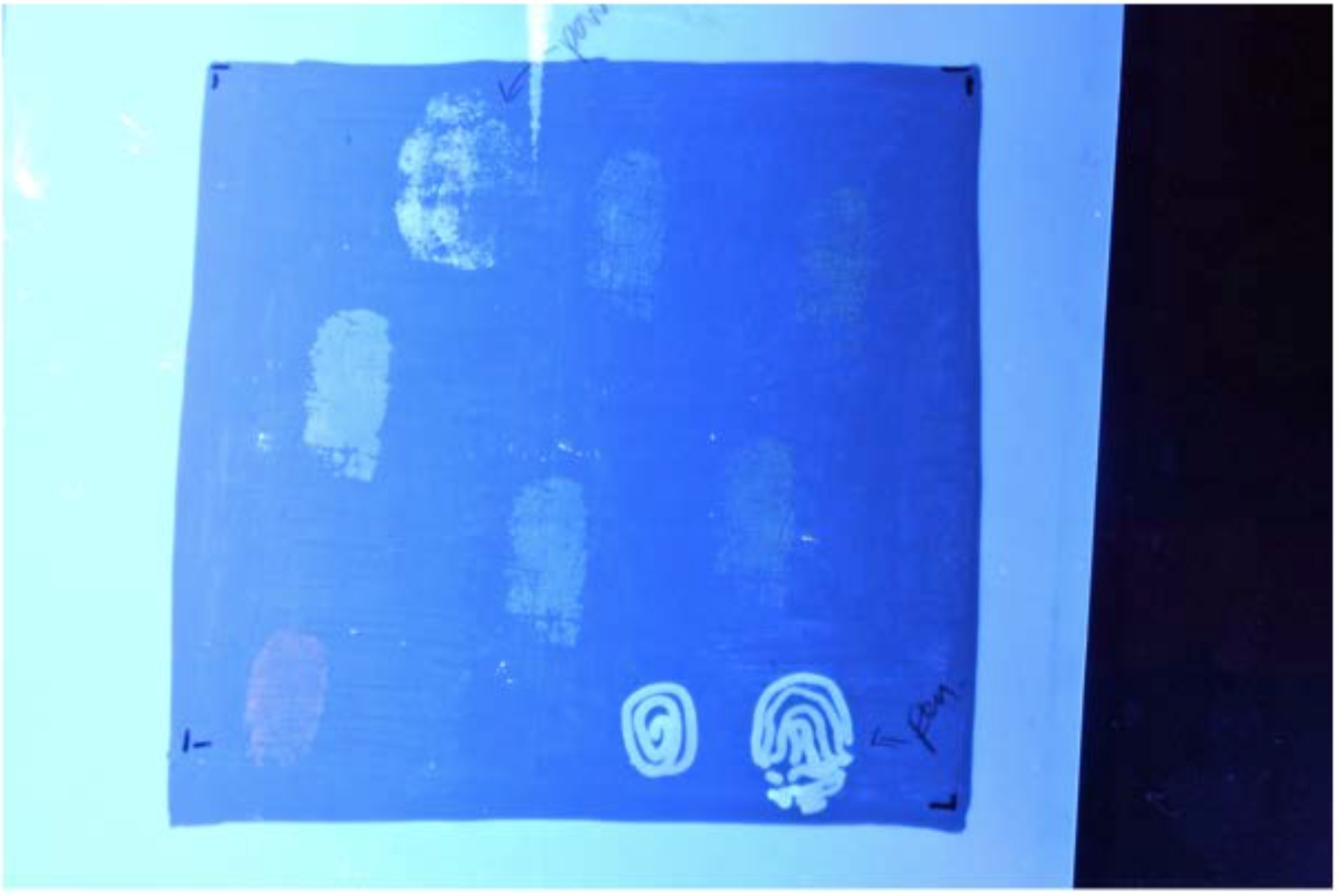

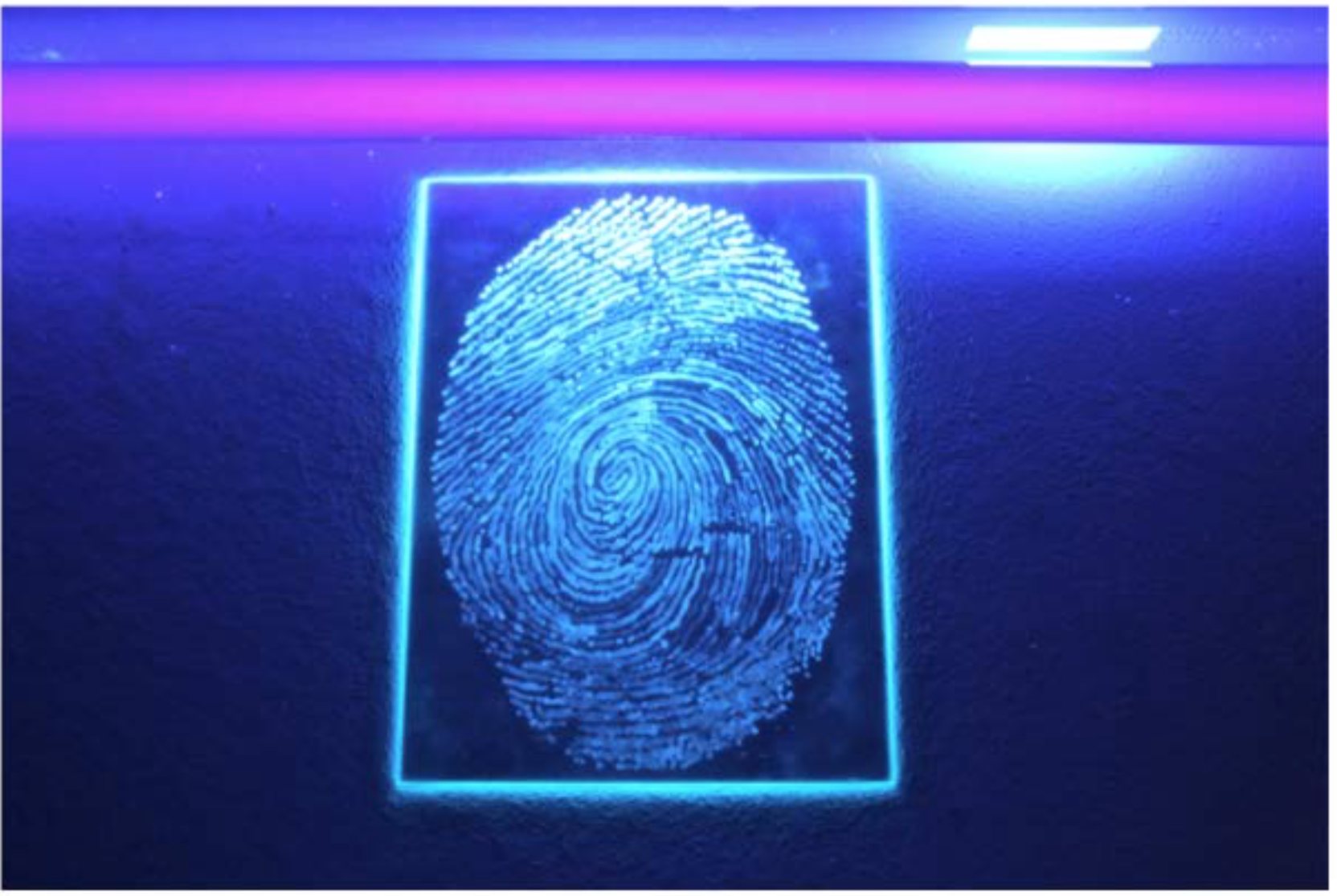

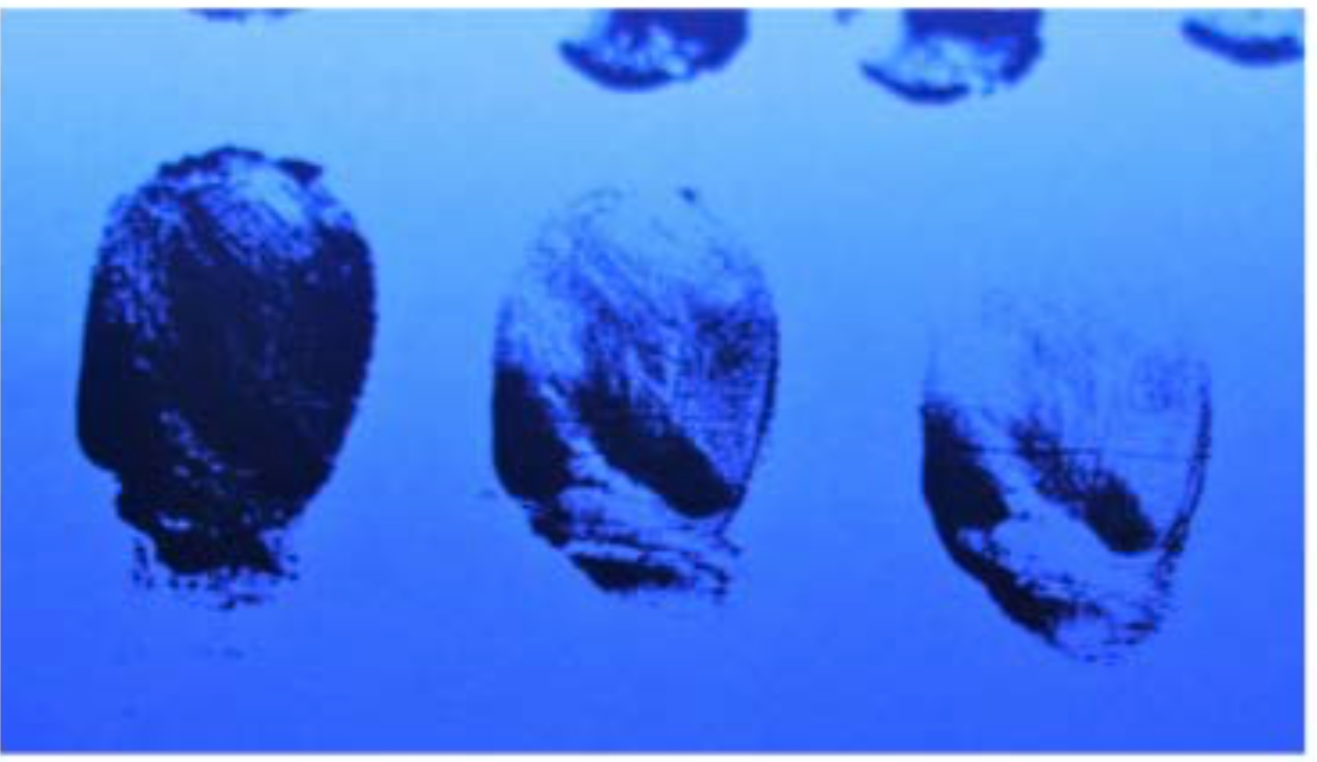

Exploring the notion of human trace, focus is narrowed towards evidence of direct physical contact with surfaces. Fingerprints and foot impressions are accidental, mass produced bi-products of often fleeting daily activities. While the event may be transitory, the marks and impressions, though never indestructible, outlast and document the event and thus considerations have been given processes of preservation. Juxtaposition is central to the practice, contrasting the unintentional and intentional, synthetic and organic and the bi-product and desired outcome.

Contextual Research

Due to strong thematic equivalences to aspects of science and forensics, primary contextual research, knowledge and transferable skills were gained through first-hand contact with University Chemistry and Leicestershire Forensic Departments. Experimentation with specialised materials and processes furthered consideration of their utilisation in fine art outcomes, merging boundaries of subject specificity.

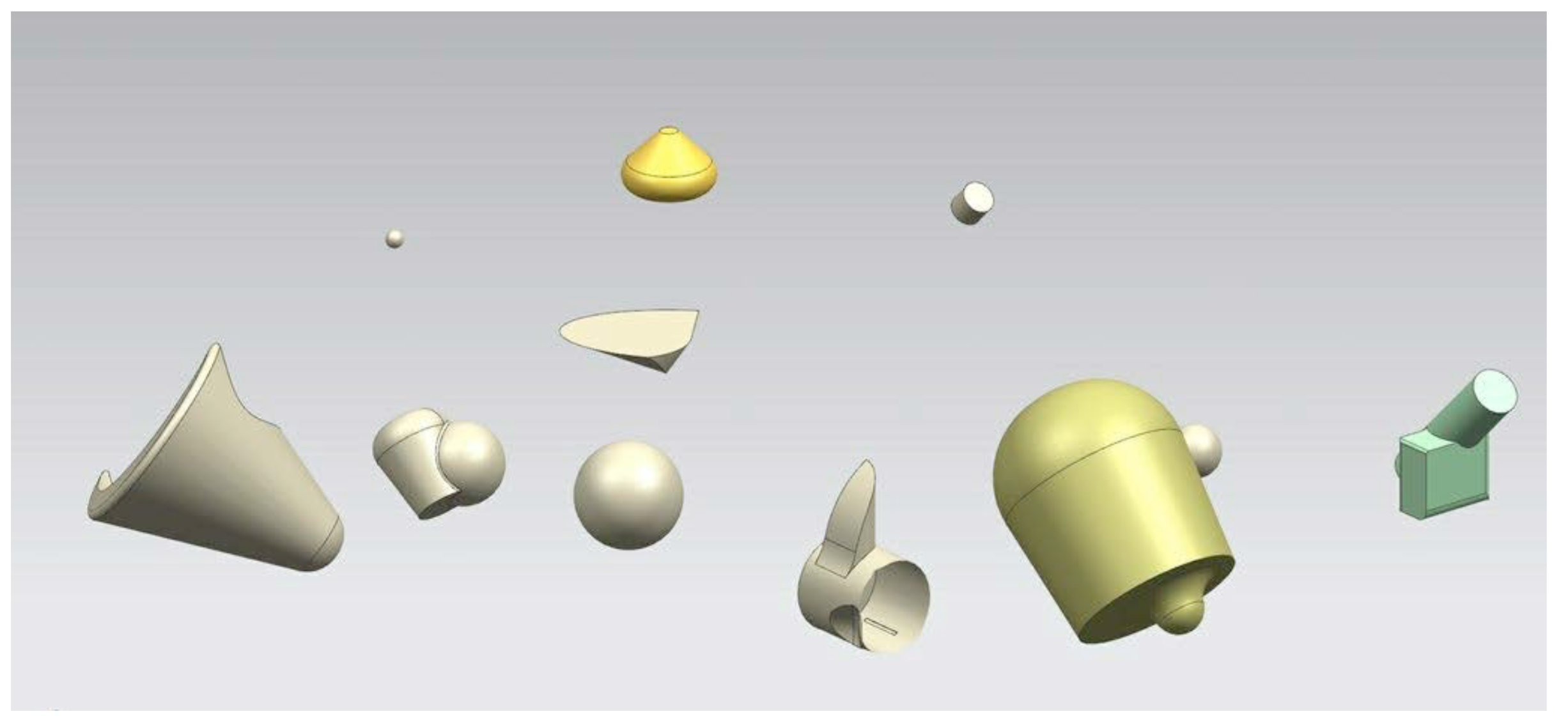

Exploration of human trace and ephemerality, encapsulating accidental and intentional marks and imprints, continue to guide and inform, in conjunction with newly acquired knowledge of forensic casting and scientific methods of exposing and documenting prints. Exploration of casting methodologies was subsequently supported by the practices of Gijs Gieskes and Christopher Locke's juxtaposing of the historic, timely and natural process of fossilisation and preservation with he employment of contemporary imagery, synthetic materials and human input.

Materials and Work Processes

The fingerprint, as one of the purest forms of trace evidence and documentation of human activity, is presented in both synthetic and organic contrasting forms.

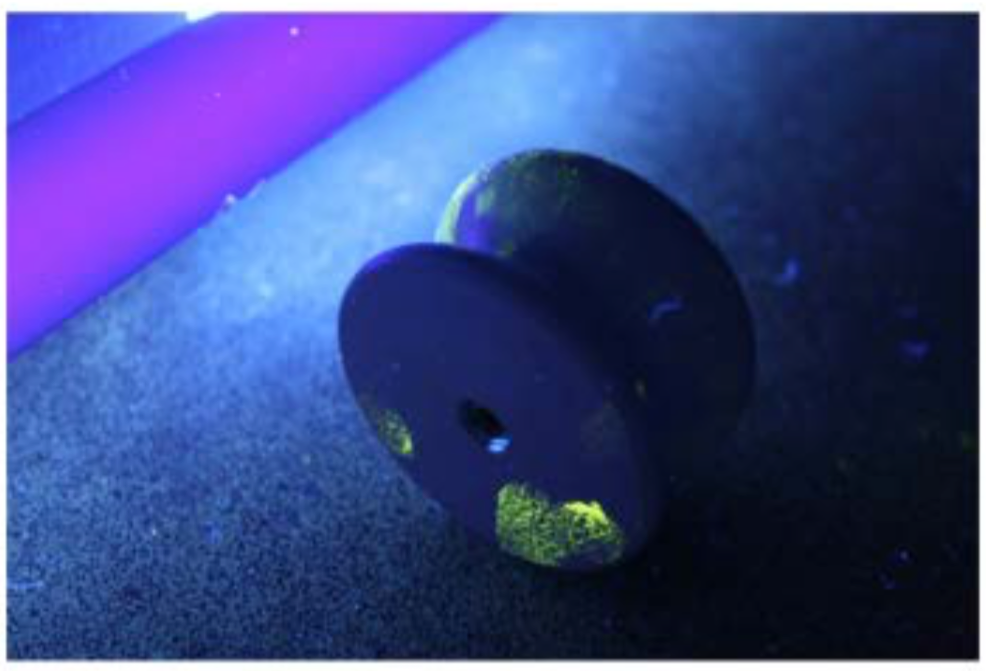

Equally repetitious, vacuum forming provides a commercial, long-lasting method of producing a solid form while contrasting the unintentional, naturally occurring, fragile prints. Natural stone and preliminary cast work as representation of the highly gradual process of fossilisation and preservation provide both juxtaposition and similarity when set adjacent to manufactured rapidly produced plastic, preserving by nature of material. Exploration of specialised forensic substances allowed for the aesthetic merging of science and art.

Actual Outcomes

The conclusion of this practice incorporates both fine art and forensic science and reflects various parallels and juxtapositions.

The two spaces present the visual subject of the fingerprint in oppositional processes, while the initial space allows for the contemplation of contrasting forms of preservation. The fading quality of the vacuum formed image reflects the ultimate non-permanency of the trace itself. The work does not aim to suggest the permanent encapsulation of human traces, but merely reflects the fragility of everyday events and use of trace to document and preserve the ephemeral gestures.